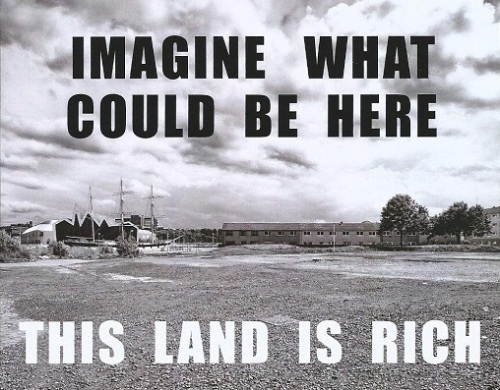

The Graving Docks: nature has already reclaimed this forlorn, abandoned relic of Govan’s shipbuilding heritage (© Tom Manley).

Placemaking is a concept with which I was unfamiliar until a few years ago, when I started getting involved with some of the heritage projects at Govan. Many of these projects have a creative focus in which art, architecture, history and archaeology work together to produce something tangible and beneficial for local people. Placemaking is another ingredient which can be added to the mix, being essentially a holistic approach to improving the built environment. It can be defined as ‘a multi-faceted approach to the planning, design and management of public spaces. Placemaking capitalizes on a local community’s assets, inspiration, and potential, with the intention of creating public spaces that promote people’s health, happiness, and wellbeing.’ *

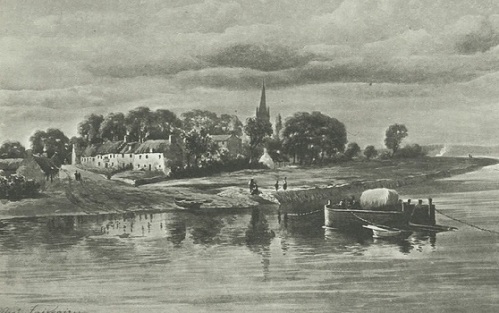

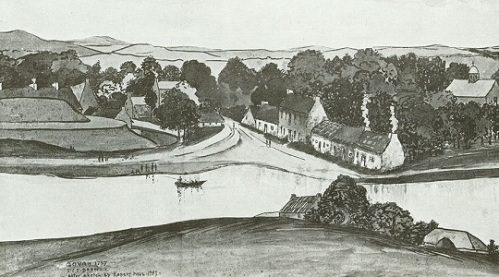

An insightful commentator on the role of placemaking at Govan is photographer Tom Manley. Tom’s background is in architecture, which will come as no surprise to anyone who has seen his brilliant images of historic buildings. But Tom also has an eye on the wider perspective and has maintained a focus on urban regeneration issues: how an area finds appropriate ways of transforming itself. In both photography and writing he has a knack for identifying the layers of memory that lie beneath or behind the frontages of an urban landscape. At Govan, this awareness has inevitably brought him into contact with the town’s ancient past, and with an era when the original riverside settlement lay at the heart of the kingdom of Strathclyde.

The kingdom’s most visible legacy is a collection of sculptured stones at Govan Old Parish Church. Completion of a project to re-display these impressive monuments has enabled better public appreciation of their carvings. The re-display has been further enhanced by a graceful textile screen created by the Weaving Truth With Trust project. Seeing the stones in their new settings is obviously recommended, but the next best thing is a browse through Tom Manley’s photographs.

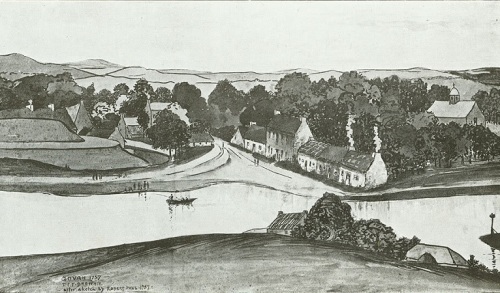

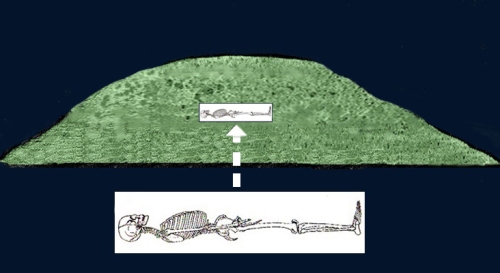

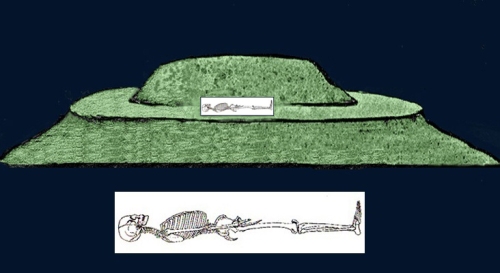

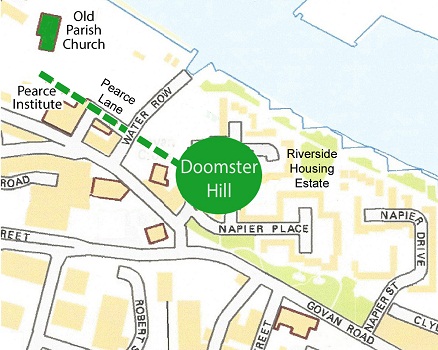

Tom has also been active in a campaign to preserve the historic area around Water Row which includes an ancient river-crossing, an early medieval ceremonial pathway and the site of the Doomster Hill – a massive artificial mound, demolished in the nineteenth century. The hill was almost certainly used as a venue for public assemblies 1000 years ago.

Looking east from Water Row over the Doomster Hill site. On the left, across the Clyde, the Riverside Museum can be seen in the distance (© Tom Manley).

Tom’s recent thoughts on placemaking at Govan can be seen in an article in the architectural journal Edge Condition, in which he takes the reader on a photographic tour of landmarks and townscapes. Positive connections between place and people are highlighted alongside challenging issues such as economic decline, derelict space and poor urban planning, Reminders of an ancient past can be seen in two images of Matt Baker’s ‘Assembly’ artworks which mark the probable outline of the Doomster Hill, together with a view (shown above) of the east side of Water Row where the great mound once stood.

Tom’s article, presented as a ‘photo story’, eloquently captures the unique character of Govan. Well worth a look if you’re interested in the town’s multi-layered history, rich architectural heritage and strong sense of community. Click the link below to access the journal, then turn to page 74 for Tom’s article ‘Govan: a reconnection’.

* * * *

I am grateful to Tom Manley for permission to reproduce the two photographs.

Take a look at Tom’s website to see more of his work at Govan. One of his stunning images of the early medieval carved stones appears in my latest book Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age.

* The quote at the top of this blogpost is from Wikipedia. See also the definition of placemaking at the website of PPS (Project for Public Spaces).

* * * * * * *