Most of the early medieval sculptured stones at Govan are recumbent cross-slabs, designed to be placed horizontally on top of graves. The basic decoration on these monuments is a cross surrounded by interlace patterns, with the cross itself usually being plain or – in some cases – decorated with more interlace. Most of the slabs have a plain border running around the edge.

All of the Govan cross-slabs were carved in the Viking Age (9th-11th centuries AD) as memorials to people of high status. All of them once lay in the graveyard of the old parish church (Govan Old) before being brought inside in modern times. A thousand years ago, Govan was the premier religious and ceremonial site in the kingdom of Strathclyde and it is likely that the ancient burial ground around the church was used not only by the kingdom’s nobility and senior clergy but also by the royal family. How many cross-slabs, hogback stones and free-standing crosses once stood there is unknown but more than 30 have survived – a remarkable figure at a site in the midst of so much modern urbanisation and heavy industry.

An example of an angle-knobbed cross-slab at Govan Old Parish Church.

A few of the surviving cross-slabs have an “angle knob” carved at each corner. The significance of these circular features is unknown but one plausible explanation is that they represent the corner-posts of a box shrine, a type of tomb in which the remains of an important person were interred so that the whole thing could be put on public display and suitably venerated. A cross-slab with similar angle knobs survives at Inchinnan, some miles west of Govan, which was also a major religious centre in Strathclyde. At both sites the stonecarvers may have been evoking the shape of a well-known shrine that was on public display somewhere within the kingdom. If so, this original “inspirational” monument is now lost, nor do we know where it was located or whose remains it contained. Assuming it existed, we might wonder if it housed the bones of a famous saint – perhaps even the mysterious Constantine to whom the parish church of Govan is dedicated. Constantine is presumed to have lived in the 6th century AD. The popular modern belief that his tomb is the richly carved sarcophagus discovered at Govan Old in 1855 has no basis in ancient tradition and is actually little more than a guess.

Long after the kings of Strathclyde had passed into distant memory, the ancient gravestones at Govan were re-used by a number of local families as memorials to their own deceased relatives. These families were regarded as having special status within the community, either because they held ancestral rights to farmland or because they were successful in their chosen trade. They began to re-use the ancient stones as a way of displaying their importance and prosperity. By associating themselves with the ornate sculpture of a remote past they were reinforcing their own social position. This kind of monumental recycling occurred during the 1600s and 1700s, a period when the main economic activities in Govan were farming and handloom weaving. The weavers were important folk and had their own guild – the Govan Weavers Society – which organised the annual Govan Fair (held from 1756 onwards). Local historian T.C.F. Brotchie, writing around 100 years ago, described the Govan weavers as “bonnet lairds” – people of prominence and importance in their own neighbourhood. It is likely that some of the recycled cross-slabs were placed above weavers’ graves.

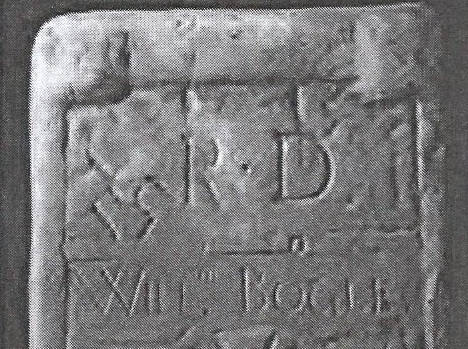

Recycling took the form of a new inscription overlaying the ancient carvings. This usually gave the initials of the deceased person, sometimes with the year of their death. In only one instance is the full name shown, the stone in question being one of the angle-knobbed slabs. It was used as the grave-marker of a man called William Bogle.

Victorian cast of the Bogle Stone. Photograph from Sculptured Stones in the Kirkyard of Govan (1899).

Who this person was, where he lived and when he died are unanswered questions. His inscription is sometimes thought to belong to the 1700s, but the style of the “W” appears on a slab re-used in 1634, so maybe William’s burial is also from around that time. People with the surname Bogle were fairly numerous across Lanarkshire in the 17th and 18th centuries and there were several branches of the family in Glasgow. One branch was associated with a place called Bogleshole near Cambuslang while another became wealthy merchants who later took part in Scotland’s trade with North America. Identifying the branch to which our William belonged is a matter of guesswork, not least because the records of births, marriages and deaths from Govan Old are incomplete and there is no register of burials for the period when the cross-slabs were recycled. However, he presumably lived within the parish of Govan at the time of his death. He may have been a weaver whose labours had elevated him to a position of status on the social ladder, earning him the right to be buried beneath one of the ancient carved stones.

Cross-slab recycled in 1634, showing a similar W to the one on the Bogle Stone.

I tentatively suggest that our William Bogle might be the one mentioned in an old document as the husband of a woman called Jonet Sheills. Jonet died in 1667 and was prosperous enough to leave behind a testament or will for the distribution of her possessions. She originally came from Partick on the north bank of the Clyde but she and William lived across the river in the Gorbals – an area formerly known as Little Govan – where William worked as a weaver. Gorbals was part of Govan parish until 1771.

While this identification is not certain (and would, in any case, be difficult to prove) it does seem to me quite possible. I’d like to delve a bit further among the various genealogical records to see if I can unearth more information about the mysterious William Bogle, not only out of curiosity but also because his story is part of the longer tale of the ancient monument on which his name was inscribed.

* * * * *

Notes & references

JR Allen & J Anderson, The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1903). Part III, p.466.

Rosemary Cramp, ‘The Govan recumbent cross-slabs’, pp.55-61 in Anna Ritchie (ed) Govan and its Early Medieval Sculpture (Stroud, 1994) [at p.56]

Catherine Cutmore, ‘An Archaeological Study of the Memorial Stones in the Kirkyard of Govan Old Parish Church’ Annual Report of the Friends of Govan Old (1997), 8-18.

Betty Willsher, ‘Govan Old Parish Church Graveyard’ Annual Report of the Friends of Govan Old (1992), 16-23.

Information on Jonet Sheills, wife of the Gorbals weaver William Bogle, came from a register of testaments for 1564-1800 which I found online.

The initials “R D” above William’s name show that this stone has been re-used at least twice.

I’ve written a couple of earlier blogposts on recycled cross-slabs: the Bellahouston Stone and Govan Cross-Slab 32.

As with the Bellahouston Stone, the name “Bogle Stone” has been coined by me as a way of identifying a monument that would otherwise be known only as a number on a list. I think such names make the Govan stones less anonymous by giving them a bit of character and personality.

And finally…. in Scottish folklore, a bogle is a kind of hobgoblin.

* * * * * * *