Today, 10th August, is the feast-day of St Blane, abbot of the monastery of Kingarth on the Isle of Bute, who died in 590. It is also the anniversary of a battle that took place in the year 756, a grievous military setback for the powerful Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria. The circumstances surrounding this battle were described by a contemporary English chronicler :

In the year from the Lord’s Incarnation 756, King Eadberht in the eighteenth year of his reign, and Unust, king of the Picts, led an army to the town of Dumbarton. And hence the Britons accepted terms there, on the first day of the month of August. But on the tenth day of the same month perished almost the whole army which he led from Ouania to Niwanbirig, that is, to the New City.

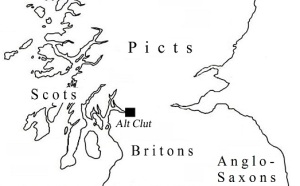

Eadberht (pronounced ‘Yad-bert’) was one of Northumbria’s greatest warrior-kings. He had already enlarged his kingdom by conquering parts of Ayrshire, probably at the expense of the Clyde Britons whose kingdom was ruled at that time from Dumbarton Rock. Over on the northeastern frontier of his realm, Eadberht faced a lurking menace in the shape of the aggressive Pictish king Unust (Oengus in Gaelic). Both had tried, on separate occasions, to gain territory from the Britons, but in 756 they decided to pool their resources for a joint attack on Dumbarton. Their aim, no doubt, was to neutralise the Clyde king Dyfnwal so that he could no longer defend his lands from being plundered or annexed.

On 1st August, so the chronicler tells us, the combined Anglo-Pictish army marched to Dumbarton and forced the Britons to surrender. King Dyfnwal (pronounced ‘Duv-noo-wal’) would have had little choice but to pay homage to Unust and Eadberht. Separately, he might have been tempted to take each of them on – his father had famously defeated Unust at Mugdock in Strathblane six years earlier – but together the allies must have looked invincible. Dyfnwal’s capitulation would have involved a formal ceremony with rituals such as gift-giving and oath-pledging. It would have been staged at a prominent ceremonial site within his kingdom, and no site was better suited for this purpose than the Doomster Hill at Govan. My guess is that this is where the formal surrender took place on Sunday 1st August, 756.

Nine days later, on Tuesday 10th, the feast-day of St Blane, the Northumbrian army was ambushed after leaving Ouania. The latter is an artificial Latinised form of a place-name that is believed to be the original form of the name Govan. Early medieval chroniclers often rendered unfamiliar place-names into Latin because this was the language they used in their writings. Here, Ouania is simply an invented Latin form of a place-name that probably looked strange to an English chronicler reporting the events of August 756. The main language of Clydesdale in early medieval times was Cumbric, a Celtic language closely related to Welsh. In Cumbric the original name of Govan was something like Gwovan, which in Welsh would be Goban (go + ban = ‘little hill’). Interestingly, the English chronicler seems to have devised the pseudo-Latin name Ouania not from Cumbric Gwovan but from a different word Ouvan (the ‘u’ in Ouania represents the spoken letter ‘v’). Experts in Celtic place-names suggest that Ouvan may have been the Pictish name for Govan, in which case the chronicler presumably got his information on the campaign of 756 from a Pictish source. This is consistent with his spelling of Unust which is almost certainly the original Pictish form of the king’s name.

What the chronicler seems to be saying is that the Anglo-Pictish force separated after receiving Dyfnwal’s surrender, each army then returning home to Northumbria and Pictland respectively. Both Eadberht and Unust may have begun their homeward journeys at Govan, from where the Picts could easily ford the Clyde to pick up one of the main routes to Fife or Perthshire (via Strathblane or the Kelvin Valley). From Govan the Northumbrians likewise had a choice between an eastward route through English territory in Lothian or a southeastward one along Clydesdale to the headwaters of the Tweed. The chronicler doesn’t say which route Eadberht chose but does indicate that a place called Niwanbirig, the New City (or Fortress), lay somewhere along it. Before reaching Niwanbirig the Northumbrians were attacked and, in the ensuing battle, were almost wiped out.

Frustratingly, we don’t know where Niwanbirig was. The name is Old English (i.e. ‘Anglo-Saxon’) and on a modern map would appear as Newbury, Newburgh, Newbrough or Newborough. There’s a Newbrough near Hexham in Northumberland and some historians think this is the place Eadberht was aiming for when he left Govan. The problem with this theory is that Newbrough probably didn’t exist in Eadberht’s time. Equally frustrating is the chronicler’s failure to identify the attackers who ambushed the English army on 10th August. Were they Northumbrian rebels led by one of Eadberht’s ambitious rivals at home? Were they Picts sent treacherously by Unust to slay his former ally? Or were they Britons from the Clyde, hell-bent on avenging the humiliation of their king? It’s a puzzle to which we may never know the answer.

* * *

Notes & references

* The Dyfnwal mentioned here was an earlier namesake of the tenth-century king who appears in Jim Ferguson’s story The Bride of King Dyfnwal (see previous blogpost).

* The chronicle describing these events was compiled at a Northumbrian monastery in the beginning of the ninth century, using information from older sources. Neither the author nor the place of compilation are known but the text was later incorporated into the History of the Kings attributed to the twelfth-century writer Symeon of Durham.

I examine the events of 756 on pages 153-6 of my book The Men of the North: the Britons of Southern Scotland.

James Fraser deals with the same topic on pages 316-8 of his book From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795.

For a detailed study of the place-names, see Thomas Owen Clancy’s article on the Friends of Govan Old website.

* * * * * * *

Read Full Post »