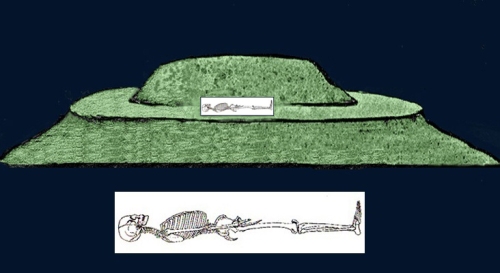

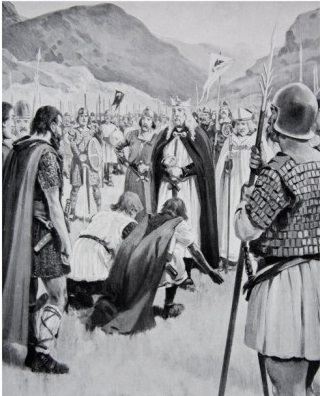

Athelstan receiving oaths at the meeting of kings in 927 (illustration by John Archibald Webb, 1866-1947)

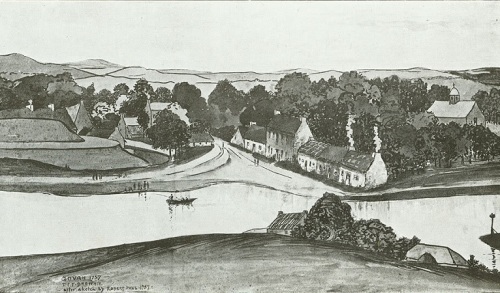

From the late ninth century to the mid-eleventh, when Govan was the chief ceremonial centre of the kingdom of Strathclyde, the king and his family probably spent their Christmases there. As the second most important date in the Christian calendar, December 25th was an opportunity for early medieval monarchs to display their religious credentials. It was a day when the entire royal entourage or court, comprising all the chief nobles and senior clergy of a kingdom, gathered together for a solemn mass. In Strathclyde, this Christmas service would most likely have taken place in the ancient church where Govan Old stands today. The mass would have been followed by a suitably lavish festive feast, perhaps at the royal hall across the river in Partick. We know of one year, however, when the king of Strathclyde spent Christmas in another land, far from the familiar fields of his own country.

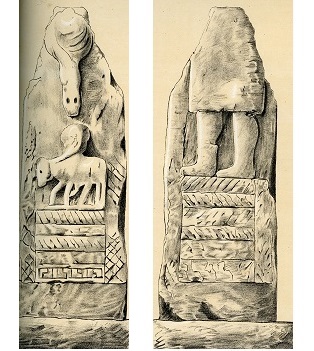

The king in question was Owain, whose reign spanned the 920s and 930s – one of the most turbulent periods in Britain’s history. We first hear of him in 927, when he attended a meeting of rulers at the River Eamont near Penrith on the southern border of his realm. The meeting was summoned by Athelstan, king of England, the most powerful ruler in Britain at that time. Athelstan’s ambitions surpassed even those of his illustrious grandfather Alfred the Great, for he wanted to be acknowledged as ruler of the whole of Britain, from Orkney to Cornwall. He wanted all other folk – English, Welsh, Scots, Viking settlers and Strathclyde Britons – to recognise him as their overlord. Needless to say, not everyone was happy to oblige, but it may have seemed easier to just go along with his lofty ideas, at least for a while. At the meeting beside the River Eamont in 927, a number of prominent rulers – King Owain of Strathclyde, King Constantin of Alba (Scotland), King Hywel (from South Wales) and the English lord Ealdred of Bamburgh (in Northumbria) – all gave their pledge to Athelstan. They seemingly swore an oath of friendship with him, promising not to get too cosy with his Viking enemies.

The pact of peace seems to have endured for seven years until, in 934, Constantin of Alba and Owain of Strathclyde incurred Athelstan’s wrath.They broke their pledge, so Athelstan marched north to reassert his authority. With him on this expedition were Hywel and other Welsh kings, each leading an army to bolster the English troops. In a remarkable display of military power, Athelstan led his combined forces as far north as Aberdeenshire, while his fleet raided in Caithness. Both Constantin and Owain eventually surrendered, the price of their defeat being an oath of allegiance to Athelstan. Like the Welsh kings they now became his vassals or ‘under kinglets’ (Latin: subreguli). Henceforth, their kingdoms had to send regular tribute-payments to England, while they themselves were obliged to periodically travel south to attend the English court. How often they did so is unknown but we know of at least a couple of occasions when they were among Athelstan’s entourage, either together or singly. In 935, for instance, they were both present at Cirencester in Gloucestershire, for their names appear in a list of witnesses to a charter (a document recording a grant of royal land) issued at the old Roman city. At the end of the same year, Constantin was strangely absent when the English court assembled in Dorset, at the city of Dorchester. This was in the heartland of Wessex, the ancestral domain of Athelstan’s family. Here the English king issued another land-grant, and Owain was present as a witness.

The charter in question was dated 21 December, just four days before Christmas, so we can be fairly sure that Athelstan had decided to spend the festive season in Dorset. His whole entourage – family members, chief nobles and senior bishops – would have been obliged to remain with him, regardless of wherever else they wanted to be. So, too, would the vassal rulers from other lands, the subreguli who owed allegiance to him. Constantin of Alba didn’t turn up, presumably because he had shaken off the English yoke, but Owain and Hywel and other kings were in attendance. No doubt Owain wished he was spending Christmas in Govan, celebrating the Nativity with his own family and friends, but it was not to be. However, at some point in the following year, he followed Constantin’s example by rejecting English overlordship. These two kings then formed an alliance with the Vikings of Dublin and began to plot Athelstan’s downfall. In the autumn of 937, the three allies invaded England in great strength. Athelstan responded by defeating their combined armies at Brunanburh, one of the most famous battles of the early medieval period.

* * *

Appendix: The Christmas charter

Charters were usually written in Latin by scribes attached to the king’s court. The majority are records of gifts of royal land to monasteries. A detailed description of the land being granted was normally followed by a list of witnesses who ‘agreed and subscribed’ the grant, each marking his or her attendance with a small cross. The first name on the list was the grant-giver himself (the king), followed by senior clergy, vassal-rulers (subreguli) and members of the nobility.

The charter issued by Athelstan at Dorchester on 21 December 935 recorded a gift of land to Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire. After Athelstan himself, the most important witnesses were the two leading clergymen in England: the archbishops of Canterbury and York. These were followed by the vassal-rulers, in order of seniority, with Owain of Strathclyde moving into top spot in the absence of Constantin of Alba. Hywel came next, as Athelstan’s most important Welsh vassal. After Hywel, the other Welsh kings stepped forward to mark their presence, but I’ve not included them in the extract shown here:

Ego Æthelstanus, ierarchia florentis Albionis prædictus rex, cum signo sanctæ semperque venerandæ crucis coroboravi hunc indiculum et subscripsi. + Ego Wulfhelmus Dorobernensis ecclesie archiepiscopus consensi et subscripsi. + Ego Wulfstanus Eboracensis ecclesie archiepiscopus consensi et subscripsi. + Ego Eugenius subregulus consensi et subscripsi. + Ego Howel subregulus consensi et subscripsi. + …. …. ….

[Translation] I, Athelstan, king of flourishing Albion in possession of the office, confirmed and subscribed this document with the mark of the holy and always to be venerated cross. + I, Wulfhelm, archbishop of the church of Canterbury, agreed and subscribed. + I, Wulfstan, archbishop of the church of York, agreed and subscribed. + I, Owain, under-kinglet, agreed and subscribed. + I, Hywel, under-kinglet, agreed and subscribed. +…. …. ….

The full text of this charter can be found at The Electronic Sawyer. Owain’s attendance at the English court is discussed in my book Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age (p. 83) and in Alex Woolf’s From Pictland to Alba (pp. 167-8).

The British Isles in AD 935, showing places mentioned in this blogpost.

* * * * * * *