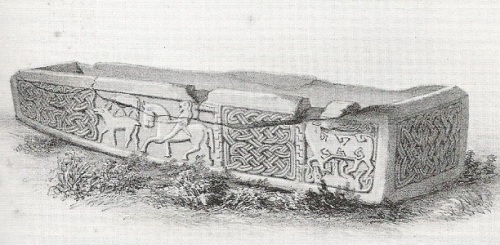

The famous sarcophagus at Govan was discovered on Friday 7 December 1855 by the sexton of the old parish church as he dug a new grave in the kirkyard. It lay a couple of feet below the surface, having been deliberately buried at some unknown date. Modern scholars now believe that it was carved around AD 900, that it orginally contained a human corpse and that it was created as a public monument to be displayed and viewed. Soon after it was unearthed, perhaps within days, it was moved to another part of the kirkyard and enclosed by wooden railings. During this process it sustained significant damage, especially to the two long side-panels containing the richest sculpture. The horizontal crack seen in the drawing above (and still visible today) is the most obvious of these injuries.

The first published report of the monument’s discovery appeared in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. The author, James Cruickshank Roger, had been elected to the Fellowship of the Society in 1854. He lived at Cross Bank Cottage in Govan. Although his paper was not published in PSAS until 1857 it had evidently been presented to the Society a year earlier: the date ‘January 12, 1856’, five weeks after the sarcophagus was found, appears at the end. As well as giving a full account of the discovery Rogers included detailed descriptions of other Govan stones – notably the hogbacks – whose existence had been known for some time. The sketches that originally accompanied the paper were not, however, published alongside it, as an editorial note explained:

‘Sketches of these different sculptured stones were exhibited, and presented to

the Society ; but, as drawings of them have since been included in the Spalding

Club volume of Sculptured Stones, collected and edited by John Stuart, Esq.,

it was not thought necessary to have them re-engraved.’

The work referred to here was the first volume of The Sculptured Stones of Scotland, a two-part study edited by John Stuart, at that time the Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries. It was published in 1856 by the Spalding Club of Aberdeen, another antiquarian body in which Stuart played an active role. Highly regarded by Stuart’s peers, and still consulted by today’s scholars, Sculptured Stones was a showcase for the artistic talents of Scotland’s early peoples. Its numerous illustrations provided 19th-century scholars with an impressive gallery of Pictish symbol stones and other monuments. Among these images was the one shown at the top of this blogpost, the earliest published illustration of the Govan Sarcophagus. It was drawn by the Aberdeen-based artist and lithographer Andrew Gibb who was soon to play a major part in the production of the second volume of Stuart’s Sculptured Stones. The absence of wooden railings in the picture suggests that Gibb sketched the sarcophagus not long after it was brought out of the ground, perhaps within days of the exciting discovery (unless he simply omitted the railings from the final version). Other drawings have been produced in the ensuing years but Gibb’s fine offering, executed in his distinctive style, remains our earliest representation of Glasgow’s oldest piece of sculptural art.

* * * * * * *

References

James C. Roger, ‘Notice of a sculptured sarcophagus, and other sepulchral monuments, recently discovered in the churchyard of Govan’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 2 (1854-7), 161-5.

John Stuart, The Sculptured Stones of Scotland [Part 1] (Aberdeen: Spalding Club, 1856).

R.M. Spearman, ‘The Govan Sarcophagus: an enigmatic monument’, pp. 33-45 in Anna Ritchie (ed.) Govan and its Early Medieval Sculpture (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1994).

* * * * * * *