The rider on the Sun Stone

In an earlier blogpost I discussed the Govan cross-shaft known as the ‘Sun Stone’ which takes its nickname from a striking design carved on the reverse. The front of the monument shows a decorated cross above a man mounted on a strange-looking beast. In the same post I gave a brief description of this rider:

‘He is carrying a spear and wearing a sword: he is evidently a warrior. A curling adornment on the back of his head is usually interpreted as a pigtail.’

My description paraphrased a more detailed one provided by Ian Fisher in his authoritative paper on the Govan cross-shafts:

Below the cross, in false relief in an almost square panel, there is a rider on a galloping horse. Although the details are worn, his face appears to be turned upwards to the cross, and he has an upturned pigtail, while the horse’s bridle is visible and a spear and sword project behind the rider’s back. (Fisher 1994, 51)

Another expert observer, Alan Macquarrie, also identified the rider’s hairstyle as a pigtail (Macquarrie 2006, 5). It appears to be unique, being found only on the Sun Stone. Pigtails are not evident on any other monument at Govan, nor on sculpture from elsewhere within Strathclyde. Looking further afield, I am not aware of any pigtailed figures on Pictish sculpture. As far as I know, carvings of male Picts simply show them as long-haired, without any discernible hint of the hair being gathered and tied. The rider on the Sun Stone seems to be a one-off.

Examples of Pictish warriors (l-r): Dupplin Cross, Benvie, Aberlemno.

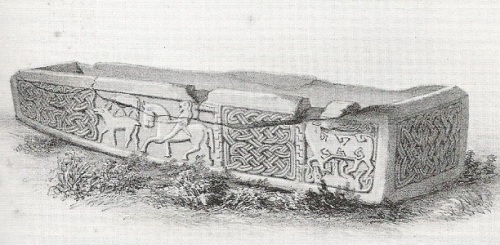

At Govan, there is only one other figure whose hairstyle can be discerned: the horseman on the Sarcophagus. He is more clearly defined than the Sun Stone rider and was probably carved a hundred years earlier (c.850-900) at a time when the stonemasons of Strathclyde were producing finely sculpted work comparable to the output of their Pictish counterparts. Like some Pictish figures, the Sarcophagus horseman is long-haired and bearded, but it is hard to say if his hair is loose or gathered. Although the detail is lacking it is possible that whoever carved him was trying to depict a ponytail. In the following century, the craftsman who sculpted the Sun Stone may have been attempting something similar when he added a curly ‘pigtail’ to the rider. Maybe this was not so much a pigtail as a crude representation of a short ponytail gathered high above the neck? Whatever it was, it was carved so prominently that it must have been a defining characteristic of the man commemorated by the stone. To those whom he left behind – his family and friends – his hairstyle was perhaps such a distinctive aspect of his appearance that they asked for it to be included on his memorial.

The horseman on the Govan Sarcophagus

If more sculpture had survived from the kingdom of Strathclyde we might be able to say something meaningful about the hairstyles worn by the wealthy folk who commissioned the stones. With only two carved figures showing sufficient detail, the most we can probably say is that long hair was not uncommon among aristocratic males of the area around Govan in the 9th-11th centuries. Some of these men wore beards; some tied their hair in ponytails or pigtails. Their contemporaries in other parts of North Britain no doubt looked very similar.

– – – – – – –

References

Fisher, Ian (1994) ‘The Govan cross-shafts and early cross-slabs’, pp.47-53 in Anna Ritchie (ed.) Govan and its Early Medieval Sculpture (Stroud: Alan Sutton)

Macquarrie, Alan (2006) Crosses and Upright Monuments in Strathclyde: Typology, Dating and Purpose Fourth Annual Govan Lecture (Govan: Society of Friends of Govan Old)

* * * * * * *

Read Full Post »