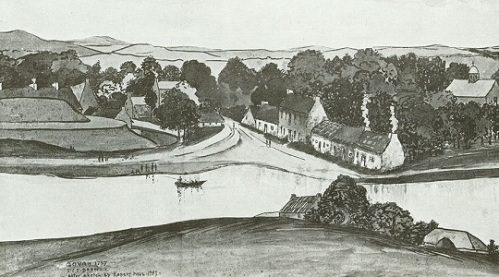

Govan in 1757, looking south across the Clyde from Partick. The Doomster Hill is on the left, with the cottages of Water Row in the centre and the parish church on the right.

Back in February I went to Govan for a meeting with Matt Baker, an artist who is closely involved with a number of creative projects relating to the regeneration of the area. Matt’s main focus is the Riverside Housing Estate on the south bank of the Clyde, directly opposite the new Glasgow transport museum. The houses of the Riverside occupy a site steeped in Govan history. Here, in the 19th and 20th centuries, stood one of the great shipyards that made Govan a world-famous centre of shipbuilding. Here, too, stood the Doomster Hill, a huge artificial mound built in ancient times as a venue for public ceremonies. It was largely because of the Doomster Hill that Matt and I arranged our meeting, for both of us have a keen interest in this now-vanished feature of the Govan landscape.

Although no trace of the hill survives, its size and shape can be discerned from old sketches made before its destruction in the 19th century. It must have been an impressive feature, a major landmark for the people of this part of Clydesdale. Its tiered or ‘stepped’ design suggests that it was meant to be used in a hierarchical way, to reinforce the social order. This was undoubtedly one of its key functions in the early medieval period, when Govan was a place of importance in the kingdom of the Clyde Britons. During a public ceremony in the 10th century we can imagine the king of Strathclyde standing on the summit of the hill, surrounded by his leading henchmen and the chief clergy of the realm, looking down on the warrior-nobility assembled on the tier below, and on the ordinary folk gathered on the lower ground around the base. The power and authority of the monarch would thus be emphasised in a strikingly visible way, as he stood in this high place to perform the formal rituals of kingship: lawmaking, gift-giving and the dispensing of justice.

After the fall of Strathclyde in the 11th century and its absorption into the kingdom of Scotland the ceremonial mound at Govan lost its royal significance but continued to be used in a local context. Its later name ‘Doomster Hill’ indicates that it was a venue where ‘dooms’ (laws) were enacted, presumably at courts answerable to local lords appointed by the Scottish kings. Eventually it fell into disuse, becoming a place associated with folklore and legend. Children pressing their ears to the grassy slopes of the hill believed they could hear fairies moving around inside.

The industrialisation of Govan In the 19th century meant that the old hill soon found itself surrounded by a growing urban sprawl. A reservoir for a nearby dye-works was dug on the summit but the greatest threat came from the shipbuilding industry that sprang up beside the River Clyde. The expansion of the shipyards meant that the hill soon became an obstacle to progress. Sometime around 1850 it was demolished and the site was levelled. The destruction was so complete that no trace of this enigmatic feature survives today, nor can its exact position be deduced. All that can be said for certain is that the Riverside Estate now occupies a part of Govan where the Doomster Hill once stood.

One of Matt Baker’s current projects at the Riverside is the aptly-named Assembly, a public artwork using landscaping and sculpture to mark three possible locations of the Doomster Hill. A couple of days ago Matt posted a preview of this fascinating project at his blog. The preview has an extract from a ‘Govan timeline’ (a document he and I have been working on) together with images of his designs for the artworks. One photograph shows one of the three stone bases upon which the sculptures will be mounted. The bases are curved to represent the outline of the Doomster Hill and are being built with cobbles salvaged from the industrial complex that formerly occupied the site. Assembly is therefore an apt name for this project, recalling not only the great public gatherings of ancient times but also the summoning of workers to the shipyards that were once the lifeblood of modern Govan. The project itself fits neatly into Matt’s overall vision for his work at the Riverside Estate by ‘re-invoking the power and significance of the land that people live on’.

* * * * * * *