One of Matt Baker’s ‘Assembly’ sculptures (the curve of stone marks the approximate outline of the Doomster Hill)

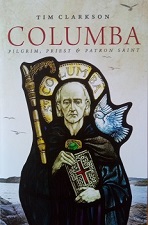

Last Saturday, November 23rd, I visited Govan to participate in a day of very interesting events. The day was just one part of an entire weekend of talks, tours and conversation around a number of heritage projects under the

Hidden Histories banner. My own involvement was with a project called ‘Re-imagining the Govan Heritage Trail’, which aims to re-vamp an existing trail by creating a number of smaller walks dealing with different aspects of the town’s rich history. The project has been initiated by artist Tara S Beall as part of a practice-based programme of doctoral research with the University of Glasgow and the Riverside Museum. Staff from the Museum are closely involved in the Heritage Trails project, together with representatives from other local organisations and community groups. I was invited by Tara to give input to a new trail dealing with ancient times and the period when Govan was a major royal centre in the kingdom of Strathclyde.

A week or more of events ran from 15th to 24th November. As well as the trails project, two others were also celebrated as part of the Hidden Histories venture: Women’s Histories & Protests on the Clyde and Isabella Elder – Great & Good (Mrs Elder was the wife of shipbuilding magnate John Elder). The busy schedule for Saturday 23rd included an afternoon walk along the Ancient Govan trail, followed by an evening of talks in Govan Old Parish Church.

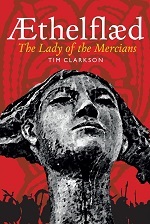

The new trail is more than a tour of the area’s early history. It’s a quest for the ‘Thirteen Treasures of Govan’, a collection of objects dotted around the town or in the Riverside Museum across the Clyde. The idea comes from the legendary Tri Thlws ar Ddeg Ynys Prydain (‘Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain’), a list of magic items associated with figures famed in the lore of medieval Wales. Many of the Welsh Thirteen Treasures have a connection with North Britain, and a few have a connection with Strathclyde. These form a nucleus around which the Thirteen Treasures of Govan have been created.

Cover of fold-out leaflet for the new heritage trail

The Thirteen Treasures of Govan are as follows. An asterisk indicates an item on the original Welsh list.

1. The Ring of Queen Languoreth, wife of Rhydderch Hael, king of Dumbarton.

2. The Cauldron of Dyrnwch the Giant. *

3. The Crozier.

4. The Whetstone of Tudwal, father of Rhydderch Hael. *

5. The Harp.

6. The Horn of Bran. *

7. The Chessboard of Gwenddoleu. *

8. The Canoe.

9. The Halter of Clyddno Eiddyn. *

10. The Cloak of Arthur. *

11. The Ship.

12. The Bell of of St Mungo of Glasgow (St Kentigern).

13. The Sword of Rhydderch Hael. *

The objective of someone embarking on the quest is to locate the Thirteen Treasures in their present-day locations, so that they can be pointed out to none other than Merlin, who will then be able to take them away for safekeeping. Some items are fairly easy to identify: the Canoe, for example, is a hollowed-out logboat retrieved from the Clyde and now displayed in the Riverside Museum. Others are concealed in more subtle ways: the Cauldron, upside down, is now represented by the upper part of the Aitken Memorial Fountain (an impressive piece of Victorian street adornment at Govan Cross). Merlin himself may have been a native of North Britain and is sometimes associated with Strathclyde. One legend says that he met St Mungo of Glasgow, while another has him being hunted by King Rhydderch, who is identified in one tradition as the father of St Constantine of Govan.

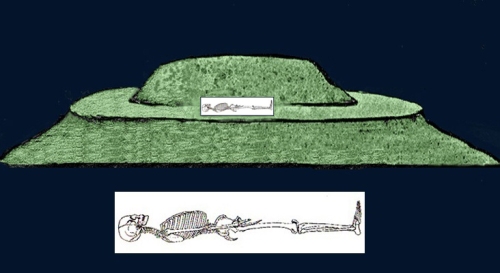

The Aitken Memorial Fountain

The trail will give visitors plenty of entertainment, while introducing them to Govan’s rich heritage. Along the way, they will meet genuine relics from early medieval times, such as the ‘Viking’ hogback tombstones and the ornately carved Sarcophagus, as well as a reminder of the Doomster Hill which served as a ceremonial venue for the kings of Strathclyde. Items such as the Horn of Bran, represented on the trail by the siren of the Fairfield shipyard, connect the glories of the remote past with those of the shipbuilding era. Fairfields is now part of BAE Systems and its future has recently come under the spotlight in the UK media.

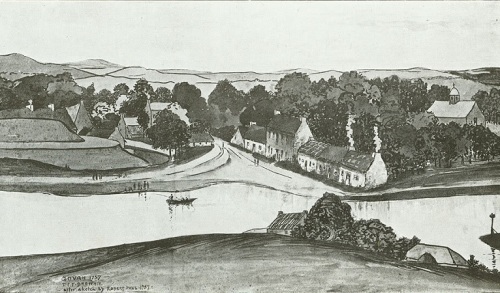

Last Saturday’s inaugural walk along the Ancient Govan trail was led by Tam McGarvey of the GaelGael Trust (a community heritage organisation who build wooden boats based on old Scottish vessels such as the birlinn or Highland galley). Tam guided an enthusiastic group of people from a starting point at the Riverside Museum to Govan on the opposite bank, via a ferry which was laid on especially for the weekend’s events (it’s usually a seasonal service). The tour was a great success, and Tam was an excellent guide. With his deep knowledge of local heritage he was able to make connections between different layers of history, drawing comparisons between the era of industrial greatness and its ancient precursor.

Tall ship ‘The Glenlee’ moored on the Clyde at the Riverside Museum

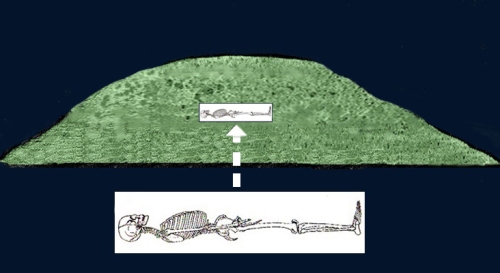

In the evening, a larger group gathered inside Govan Old Parish Church to hear three talks relating to local heritage. The first, on Ancient Govan and the Thirteen Treasures heritage trail, was given by me. The second was presented by public artist Matt Baker, who gave a virtual tour of his evocative heritage-related sculptures around the Riverside Housing Estate. One of Matt’s artworks is called

Assembly and commemorates the long-vanished Doomster Hill – a place of assembly in the time of the kings of Strathclyde. The third presentation was a screening of archive films of old Govan, with a commentary by Liam Paterson from the Scottish Screen Archive. It was a very interesting evening, clearly enjoyed by everyone who attended. Tara and the team did a great job in bringing it all together.

Afterwards, a few of us ambled across the street to continue our conversations in a corner of Brechin’s Bar. Adjourning to this characterful old tavern seemed a good way to end what had been a fascinating and fruitful day of heritage events.

Lapel badge for the new heritage trail

* * * * *

Notes & links

I would like to thank Tara Beall for inviting me to participate in the project, and also Maria Leahy and Alice Gordon for audiovisual support during my presentation at Govan Old.

A project overview of ‘Re-imagining the Govan Heritage Trail’ can be found on the Hidden Histories website

– which also advertised Saturday evening’s programme and a schedule of the entire weekend’s activities.

The same site has a useful article by Frazer Capie of the Govan Stones Project on the ideas behind the Thirteen Treasures heritage trail.

Matt Baker’s public artworks in Govan can be seen at his website Sacrificial Materials.

To keep up-to-date with these and other projects, take a look at the Glorious Govan Facebook page or follow the Govan Beacon on Twitter.

Traditional boat-making and other craft activities undertaken by the GalGael Trust are described on their website.

The Scottish Screen Archive is part of the National Library of Scotland.

* * * * * * *